MOOSE JAW — The burrowing owl is one of the most endangered birds in Canada’s prairie grasslands, but the birth of three owlets means a new generation can act as symbols of hope and conservation.

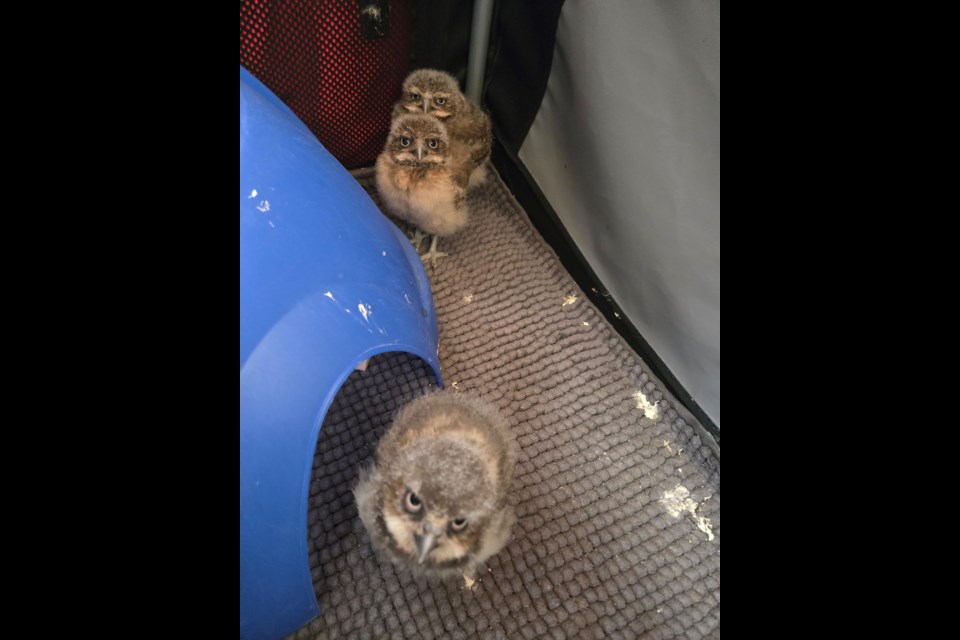

The Moose Jaw Exhibition Company announced recently that the Saskatchewan Burrowing Owl Interpretive Centre (SBOIC) had hatched a trio of birds — Blue, Pinkie and Baby — and would use them to inspire and educate the public about the species.

“It’s exciting. We’re always happy when we see some new babies,” bird handler Lori Johnson said during an interview.

It is important to have new babies to perpetuate the species, while centre staff will hand-raise them to act as ambassadors to create discussions about the challenges they face in the wild, the negative factors that affect them and what can be done to preserve them for generations to come, she continued.

Johnson will take these birds to public events where kids and adults can meet them, have an up-close look at an endangered species and learn about their place on the prairie grasslands.

“So it helps foster that connection,” she remarked.

Raising baby owls is similar to having a newborn baby human at home, as staff must feed the animals every three to four hours until they’re roughly a month old, Johnson said.

Once they’re more mature, they can go longer between feedings, while centre staff can start introducing them to more humans and providing them with new experiences.

“Usually … we’ll take the youngest from the nest, so they could be anywhere between five and seven days old when we take them,” she continued. “So about now, they’re probably hitting that one-month mark.”

“Imprinting” is the process of raising the animal and having it see the human handlers as the parents, Johnson explained. These birds will act differently from wild-born animals since they will think they’re “tiny little humans” because of how they were raised.

“It’s an ongoing process. When they’re this young, you’re basically their caregivers,” she continued. “And as they start to age, we start teaching them some different things and exposing them to different things, just like their wild parents would do.

“We’re going to be their companions and caregivers for the rest of their lives.”

These birds will act as symbols of hope and conservation because of their species’ endangered status, so increasing their numbers is always beneficial, Johnson said. Even though Blue, Pinkie and Baby will live in captivity forever, they are still important for their species’ survival and vital in educating people in how they can support the animals.

“We’re always hopeful that these owls will continue to make a difference in the Canadian wildlife and how we as people view them,” she continued. “And, we can start taking more steps to ensure that these guys always have a safe home in the wild.”

With a chuckle, Johnson said centre staff chose the names Blue, Pinkie and Baby because of the coloured bands on the birds’ legs and the fact that one animal is smaller than the others. However, those names might change, especially once staff officially know the sexes of the owls.

The centre will retire the owls from their roles as public ambassadors once they start showing signs of fatigue in meeting people, display physical limitations or show other behavioural issues, Johnson added.

Visit www.skburrowingowl.ca for more information about the Saskatchewan Burrowing Owl Interpretive Centre.