Who am I? It’s a simple question with a myriad of complicated answers.

“Indigenous identity is complicated and it’s messy. And for some reason I wanted to write fiction about it,” said Lisa Bird-Wilson.

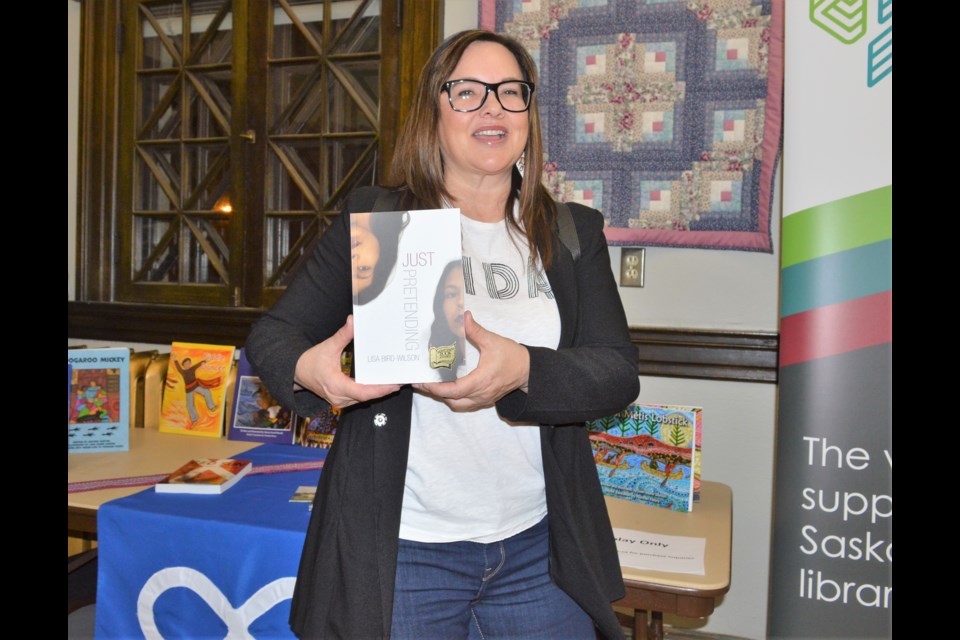

Bird-Wilson’s first short story collection, Just Pretending, was Saskatchewan’s Book of the Year in 2014 as the author earned four Saskatchewan Book Awards. Now, her book has been selected by the Saskatchewan Library Association to be its 2019 One Book, One Province selection.

One Book, One Province is a province-wide community reading initiative that aims to increase literacy and to create a reading culture by providing opportunities for residents to become more socially engaged in their community through a shared story.

Tuesday, Bird-Wilson’s book tour for One Book, One Province brought her to the Moose Jaw Public Library.

“The theme for this year’s One Book, One Province is identity. When thinking about identity, I learned the Cree word miskâsowin. My understanding of that word is that the concept it embodies is finding one’s origin, one’s centre, one’s identity and one’s belonging and also the value in doing that. In many ways this book is about miskâsowin,” Bird-Wilson explained. “The characters are often searching for their identities and they’re searching for belonging. Many have been adopted out or they’ve given up children themselves or are otherwise estranged from their origin and roots.”

Bird-Wilson is a Cree-Métis author who has also published a non-fiction history titled: An Institute of Our Own: A History of the Gabriel Dumont Institute as well as The Red Files, a collection of poetry. Tuesday she also read from a just completed, but as of yet unpublished collection of related short stories.

For Just Pretending, it took her time to find the proper vehicle for what she was trying to convey about her search for identity.

“I really wrote this book — at least in the beginning — out of an intense longing and a deep, deep desire to know who I was,” Bird-Wilson said. “As an adopted, Indigenous person this was really important for me. I think that when I talk about that longing and desire, I don’t think that’s an Indigenous thing, I don’t think that’s an adopted Indigenous thing, I think it’s a human thing for people to want to ask those questions: Who am I? Where do I come from? Where do I belong? It’s a question we can all ask and we can all relate to.

“That longing and desire was so profound for me and yet I found it really difficult to express. I tried to write about it in this real head-on way, as a non-fiction kind of topic and it just didn’t work. I found it was not subtle enough. It didn’t have the spark of energy I wanted it to have. I needed it to be engaging because I wanted people to engage with it, not sort of glaze over and think that this is really academic and yawn. Fiction became my way to express that confusion and that longing that I really wanted to express.”

The resulting work is 24 short stories that explore the themes of family — those that are real and those that we create.

“Finding origin, claiming space, clarifying the unclear, these are the ideas that this book grapples with,” Bird-Wilson said. “Although sometimes when I go to a reading, I only have a short amount of time, so I’ll sum things up and say: ‘This is a book about lousy mothers and it’s a book about lousy fathers and it’s a book about lousy children.’ Which is a little tongue-in-cheek.”

There is humour in Bird-Wilson’s description of her work and within the work itself, but there is also deep loss and pain from mothers who lost their children and children who grew up without their birth parents and numerous other characters navigating their way through their lives.

Bird-Wilson spoke about how court decisions have not only had a large impact on the Indigenous experience in Canada but also in how they define themselves. As an example of the lasting effects of a legal ruling, she noted that before 1985 First Nations women lost their status if they married a man who was not registered as a Status Indian and their children also lost their status. Not only did they and their children lose their connection to their language and culture, but they also became persona non grata in their own community.

“These legal rulings and these regulations, they impact our connections to culture; they impact how we are connected to the land that we come from; they impact our language and they impact our connection to our family,” Bird-Wilson said. “In addition to these pieces of legislation, of course, we’re also reverberating from those violent acts of colonialism like Residential Schools, like language stripping, banned cultural practices, removal of children, forced adoption — the assimilation agenda. Indigenous people have been forced into this position of having to reclaim and fight to protect our identity because of the systemic, colonial practices that have been intended to terminate our rights, and have been intended to assimilate us and to separate us from our identities.”

Bird-Wilson added that when she talks to a lot of contemporary urban Indigenous people, many have never been to their community of origin or have never been to their First Nation.

“This isn’t coincidental that this is happening. It’s a direct effect of colonization. It’s a direct effect of that colonial violence that’s been happening for hundreds of years,” she said. “For me, claiming who we are and claiming where we come from, are acts of resistance to those colonizing effects. Those are also acts of reclaiming our power.”