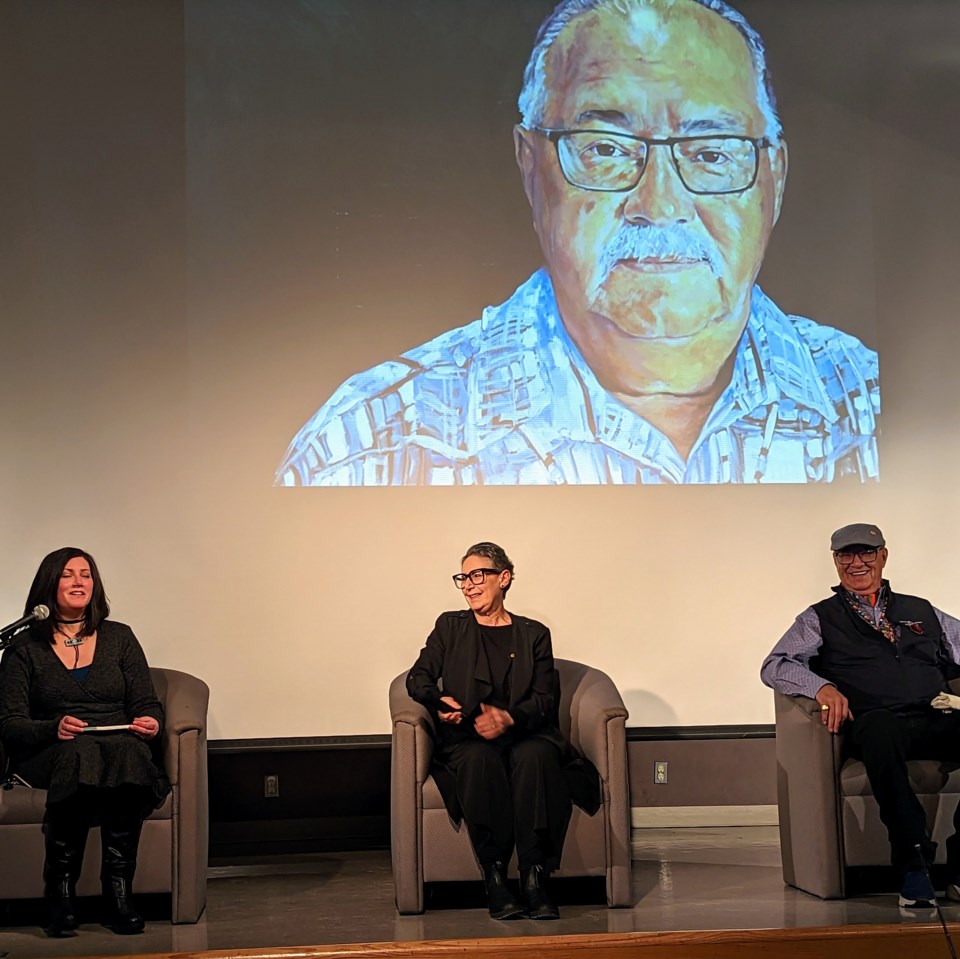

They didn’t know we were seeds by Saskatoon-based portrait artist Carol Wylie is an exhibition of 18 portraits of Holocaust and Indian Residential School survivors that opened Feb. 4 with a panel in the Moose Jaw Public Library Theatre.

The panel featured portrait subjects Elder Eugene Arcand, a survivor of Canada’s Indian Residential School system, and Kayla Hock, a survivor of the Holocaust, alongside Wylie. The panel was moderated by Jennifer McRorie, executive director and curator of the Moose Jaw Museum & Art Gallery (MJMAG).

Indigenous Elder Barb Frazier opened the panel with a prayer ceremony.

Technical difficulties prevented Hock, who joined the panel over Zoom, from participating.

“I’m always moved incredibly by the stories that the survivors tell, and I got thinking about the age of Holocaust survivors, and how important it is to have these first-hand stories and experiences expressed to us,” Wylie explained. She noted that recent political events have stirred fresh activity from Holocaust deniers.

“I wanted to find some way to capture those stories and that sense of what they had been through,” she went on. “If you observe carefully and spend time with a person and understand a little bit about them, and have an experience together … then you can create a portrait that is inhabited, to some extent, by that person.”

After Wylie’s initial idea for the project was born, a series of events pointed her to include survivors of Canada’s Indian Residential School System.

On Oct. 27, 2022, Canada’s House of Commons unanimously and historically recognized the Indian Residential School System as a genocide — the attempted erasure of an entire people.

“(We received) Indigenous sensitivity training at work,” Wylie said, “and (I learned) that (Indian Affairs Superintendent Duncan Campbell Scott, in 1910, called residential schools) ‘The Final Solution’. The only time I’ve ever heard that term was in reference to the Holocaust, so that just blew me away.”

Saskatchewan had one of the largest concentrations of residential schools, and Wylie realized that as a settler in the province, that was also a story she should tell.

As she learned more about the residential school system, Wylie saw more and more parallels, such as head-shaving, not being allowed to speak their language, separating families by force, assigning numbers rather than names, and teaching children that was happening to them was their fault.

We cannot, and should not, compare sufferings

It is important for both Wylie and her subjects that the exhibition is not considered a comparison. She shared a quote from Holocaust survivor Robert Waisman, who meets with survivors of the residential school system.

“We cannot, and we should not, compare sufferings,” Waisman said. “Each suffering is unique… I don’t compare my sufferings or the Holocaust to what happened in residential schools. We (survived) – so can you.”

“People say things like, ‘How can you even compare the experience of what happened to the Jewish people with (residential schools?)’” said Elder Eugene Arcand.

Arcand clarified that they are not comparing the experiences, but rather uniting as survivors to recognize that both communities have had to learn how to heal from deep wounds.

Shared healing is a central part of Truth and Reconciliation, a process that is immediate, real, and painful for the Indigenous peoples of Canada, he pointed out.

Arcand shared an experience he had at a University of Saskatchewan lecture where the presenter talked about ‘blameless shame.’

“Blameless shame is when you understand that as a child, you did nothing wrong,” Arcand explained. “It’s not only us. In this case, it’s focused on us as those that survived the residential school era … But it’s important that every society understand blameless shame.

“If you’ve ever experienced that type of negative activity in your life, and are carrying it, and you’re still wounded from it — understand that you did nothing wrong. That was my turning point.”

Arcand said that after his realization, he talked about his residential school experience with his wife for the first time in their then-35 years of marriage. Since then, he has worked to talk about what happened to himself and his classmates to try and help other survivors understand that what happened to them was not their fault.

They didn’t know we were seeds

“The title of the exhibition — They didn’t know we were seeds — is the second half of a poem by Dinos Christianopoulos,” Wylie explained. “And the first part starts out, ‘They buried us… They didn’t know we were seeds.

“And I thought, Well, that’s it, that exactly describes the experience of the survivors, because they were buried in the darkness of oppression. And what they made of it was not just survival, but … so many of them took their experience and talked to people, educated them about it, in the hope that the truth would come out and not be hidden anymore, and maybe that will have some impact on people in the building of their humanity.”

Wylie created her portraits the same way, starting from a dark background and bringing her subject’s faces gradually into the light.

Elder Arcand said that, in his experience, deniers of what happened in the Indian Residential School System are motivated to protect their ancestors who were involved and to defend their legacy. But, he pointed out, that urge does not help anyone.

“It’s my duty, as a living residential school survivor, to make sure the truth is known,” he said. “I don’t want pity. I don’t want people feeling sorry for me, that’s not what this is about. This is about understanding that the First Peoples of this country were persecuted.

“Let’s deal with the truth. The truth is not there to hurt. I don’t want to share the truth to hurt anyone — I’m not in that business … I am in the business of telling the truth so that we get the story straight.”

They didn’t know we were seeds is presented alongside the work of abstract artist Jonathan Forrest in the Norma Lang Gallery of the MJMAG.

The exhibitions will be open until April 30. An In Conversation event with Forrest and curators Jennifer McRorie and Kim Houghtaling will take place in-person and online at the Moose Jaw Public Library Theatre on Saturday, April 1 at 1 p.m.

Learn more about the Moose Jaw Museum & Art Gallery on its website at www.mjmag.ca/.