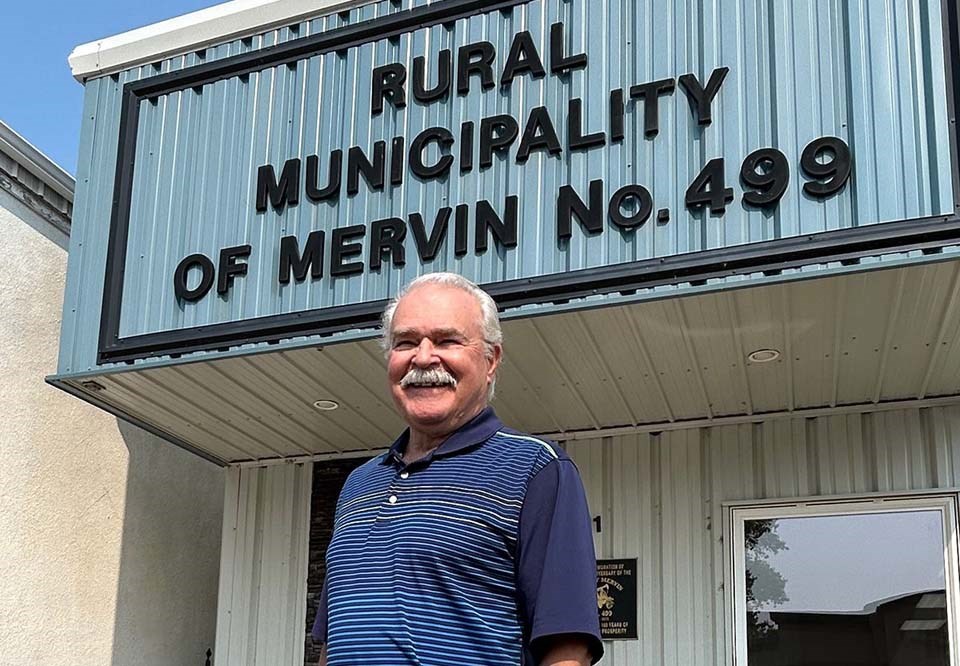

TURTLEFORD — Gerry Ritz admits that he likes to “speak his mind and never hold back.”

This is nothing new.

The 73-year-old politician has been an open book, and controversial, for the last three decades of his public life.

“He’s real, there’s no phoniness or artifice,” former Alberta premier Jason Kenney said in 2018.

“Sometimes his bluntness and humour got him into trouble, but I’d rather hear that unvarnished Saskatchewan homespun wisdom than the fakeness that comes out of Ottawa too often.”

So, during a 75 minute interview with the Western Producer in mid-July, Ritz freely shared his thoughts about his stint as Canada’s minister of agriculture, current issues within the ag industry and rural politics.

He commented on a range of topics, such as farmer support for the Canadian Wheat Board, supply management, grain industry amalgamation, Saskatchewan politics, working with former prime minister Stephen Harper and trade relations with the United States.

A poll done in 2010 by the Canadian Wheat Board found that 70 per cent of farmers supported the organization and 69 per cent supported the single desk for marketing wheat.

Other surveys from the 2000s didn’t show that level of support, but polls did find that the majority of producers backed the CWB.

Ritz didn’t believe those polls.

“I never did…. Guys (farmers) were marketing their own canola, marketing their own lentils and peas.… I would say the mood was about 80-20 (against the CWB),” he said July 18.

“Absolutely … they wanted the freedom to do what they wanted.”

There was a vocal group who supported the CWB and the status quo, including some large farmers, Ritz said, but they represented a small slice of the farm community in Western Canada.

“It was the same players, the same people, over and over again.”

Then there was the issue of supply management.

“It was discussed all the time. There were cabinet members that thought it should be done with (terminated),” Ritz said.

“But it never ever stopped us from signing a trade agreement with anybody. It didn’t.”

Talk of killing supply management didn’t get very far during the Harper era because of the value of production quotas and paying out farmers who held quota.

At some point during the Harper government, someone estimated the value of quota at $35 billion, Ritz said.

Now, it could be worth $50 billion, he guessed.

“It was a government program put in place, so … you’ve got to buy it out. You can’t just write it off,” he said.

“We sat around that fed-prov (federal provincial) table and there would be cheap shots taken, maybe by Saskatchewan/Alberta against supply management, but nobody was willing to stick their head up and say, ‘I’m going to shut it down.’ ”

Amalgamation in the grain industry

In January, the federal government approved a grain industry deal in which Bunge acquired Viterra.

Many farm groups opposed the merger of two massive companies, saying it would reduce competition in Canada’s grain and oilseed industry.

“I did not agree with the Bunge-Viterra thing,” Ritz said.

But that sort of industry concentration, where a few players control the grain trade, is a separate issue from the elimination of the CWB, in Ritz’s opinion.

“Amalgamation is going to happen, whether the wheat board is there or not,” he said.

“They couldn’t stop it. Those things (mergers) were happening beforehand.”

Saskatchewan politics

In neighbouring Manitoba, Winnipeg dominates provincial politics because the majority of legislative seats are in the city. As a result, political parties can ignore rural voters and still gain power.

Ritz is worried that something similar will soon happen in his province.

“Saskatchewan is on a bit of a precipice. By the time the next election comes around, there will be more voters in the urban quadrants than there will be in rural,” he said.

“You start to lose that rural ability to have a voice. It’s going to be problematic.”

Autonomy as a minister

Often in Canadian politics, the prime minister runs the show and cabinet ministers have little power, but during his run as agriculture minister, Ritz had plenty of autonomy, he said.

“The prime minister … gave me enough rope to hang myself, at times,” Ritz said.

But) he had some ‘short-pants’ people around him that I didn’t always see eye to eye with,” referring to young people with all the answers to everything.

Ritz used the autonomy to end the CWB single desk and work on the federal-provincial funding agreement, known as the Canadian Agricultural Partnership.

“I signed the first one.”

Country-of-origin labelling

“That was a fight,” Ritz said.

In 2009, U.S. agriculture secretary Tom Vilsack implemented mandatory country-of-origin labelling for meat products in the U.S.

M-COOL, as it was known, had a massive impact on cattle and hog producers in Canada. Animals born or raised in Canada and then shipped to the U.S. for finishing or slaughter were not eligible for a Made in the USA label on meat.

That depressed prices for Canadian livestock and meat, hurting profitability in the industry.

Canada and Mexico challenged M-COOL through the World Trade Organization, and the WTO ruled against the U.S.

The federal government also targeted U.S. states and certain industries with retaliatory tariffs.

Ritz said it was those efforts, and not the WTO rulings, that made the difference and convinced the Americans to abandon M-COOL.

“It was at the ground level, not 35,000 feet…. We went after their states and whatever (products) they exported to Canada.”

One of the trade targets was Coca-Cola, Ritz added.

“I got a call from the head of Coke in New York, saying, ‘why are you doing this to us?’ ” Ritz said.

“I said, ‘talk to your (agriculture) minister down there. He’s the one driving this.’ ”

About the author

Related Coverage

Ritz still getting things done

Bill to protect supply management passes, exporters disappointed

Supply management worth keeping: professor

Farmer shares his perspective on Canadian Wheat board demise