Ukrainian refugee Julia Maksymenko fled her country to save her children from the ravages of war but was forced to leave her husband and parents — the latter trapped behind enemy lines in Mariupol.

It was 5 a.m. on Feb. 24 when explosions awoke Maksymenko and her family, who were living in Boryspil, a suburb east of the capital Kyiv. There were no alarms to warn residents of danger, so many — including Maksymenko — returned to bed since they thought the rumbles were people celebrating with fireworks.

These were no fireworks, though, but the opening salvos of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

With the explosions continuing, Maksymenko and her husband Alexander realized this was war. So, they grabbed supplies and toys for their two daughters and moved outside the city to live with his parents.

“Every day the situation became worse. Explosions started to be more often, more often, more often. And alarm systems started to be during three to six hours (in length) … and it not stop during six hours,” Maksymenko said.

“It’s very noisy and smoky, cannot to sleep, cannot to eat because (we’re) scared. The windows were (also) shaking.”

Maksymenko, 36, spoke recently to the Moose Jaw Express about fleeing Ukraine and her journey to Canada. Since she speaks no English, she relied on Natasha Kharchenko and Amy Jane Lunov to translate.

Lunov grew up in the Yorkton-Canora area and moved to Moose Jaw several years ago, while Kharchenko moved here six years ago from Ukraine — she was an accountant — and studied at the Saskatchewan Polytechnic.

Maksymenko worked as an auditor for the Ukrainian government before the war and was preparing to return to work after two years of maternity leave when the invasion occurred.

Fleeing the country

After 10 days of living with her in-laws, Maksymenko decided to leave. She was worried that Russia would blow up all the train stations and scared that she might not be able to flee to safety.

In Ukraine, travelling by passenger train is the easiest way to move around the country.

So, Maksymenko packed up her two daughters — ages two and four — and said goodbye to her husband and in-laws. Alexander could not leave because the Ukrainian government ordered all men between 18 and 60 to remain and fight.

Maksymenko wasn’t the only person wanting to flee the country by train. Tens of thousands of people were jamming into train stations, hoping to flee the warzone. However, women with small children and the elderly were prioritized over others.

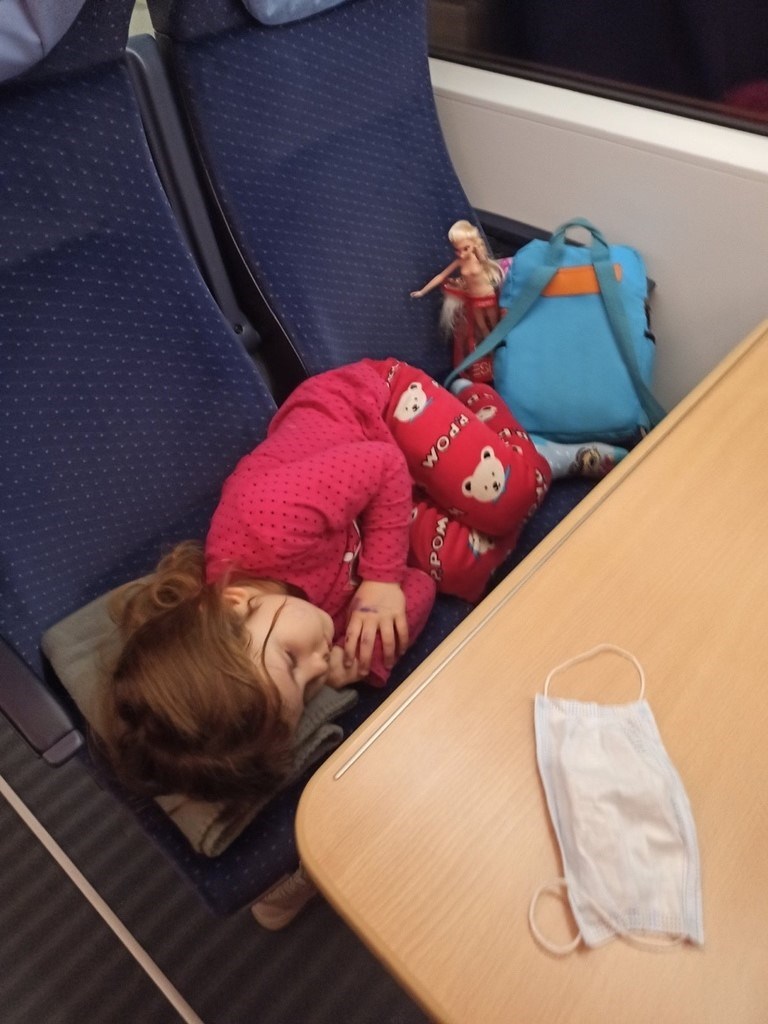

“In the train, it was shoulder to shoulder. Kids cannot even attend to the toilet because it was so crowded … cannot to sleep,” Maksymenko recalled.

Most passenger cars normally accommodate four to six people per cabin, but up to 20 people were jammed into the compartments. Moreover, while a normal train ride west would take 10 hours, this trip took 24 hours.

Crossing the border

The train took the refugees southwest to the Ukraine-Romanian border, and from there, Maksymenko and her children — with suitcases in hand — walked four hours in freezing weather to reach safety. A group of volunteers met them and took them to a school gym to sleep.

Maksymenko and her daughters stayed two days before heading to Budapest, where they caught a train to Munich, Germany and then to Dusseldorf. Her brother, Evgeniy, had his friends pick up his sister and nieces and house them while he arranged their paperwork and visas.

“(Maksymenko) stayed three weeks in Germany while the Canadian government was doing their fast paperwork,” Lunov said sarcastically.

“It (looked) like just three or four weeks, but it felt like a century,” said Maksymenko.

With paperwork and visas in hand, Maksymenko headed for the Dusseldorf airport but ran into troubles because of language barriers and cancelled flights. Her brother found a Ukrainian speaker to help his sister, with that volunteer taking the family to a church for the night.

Two days after arriving in Dusseldorf, Maksymenko took a 10-hour flight to Toronto. She and her daughters stayed two days there before flying to Regina, where they arrived on April 9 and were met by Evgeniy.

One month after fleeing her war-ravaged home, Maksymenko was finally in a safe, stable place. She spent three weeks living with her brother on a farm outside of Moose Jaw before making her first foray into The Friendly City on April 27.

Fate of parents

Throughout the ordeal, the one thing Maksymenko didn’t know was the fate of her parents, who were living in Mariupol. That city — on the coast of the Sea of Azov in southeast Ukraine — has been under constant Russian bombardment since the invasion’s beginning.

Around April 11, Maksymenko finally heard from her parents, Svetlana and Sergei Lunov, her first clue since Feb. 24 that they were alive. Her parents’ neighbour took a picture of the couple and recorded Svetlana giving a short message to her daughter.

Maksymenko played the video during the interview, while Kharchenko explained what was said.

“… the parents say goodbye because they will probably never see each other again,” Kharchenko said, emotion in her voice. “It’s like last word. They say stay safe … .

“You never know: will you see again your parents in your life? And right now, in Mariupol, very bad situation, very bad situation.”

The Lunovs have lived in their basement since March and can’t go outside because of how dangerous outside. They don’t have much food, haven’t had power or water for two months, don’t have much internet connection, can’t shower, wear the same dirty clothes and don’t sleep much because of the alarms.

They were preparing to retire when Russia invaded. Svetlana worked at the train station, while Sergei had worked at the now-besieged Azov steel plant for 35 years.

Maksymenko wants her parents to move, but they can’t since there’s nowhere to go, so they recorded a goodbye video. The only place they could flee is to Russia, 80 kilometres away.

Evgeniy is attempting to arrange passage for his parents over the Russian border to Armenia.

When asked about her reaction to the video, Maksymenko said she cried upon seeing it.

“Her heart is broken,” Kharchenko remarked. “If she didn’t have kids, she wouldn’t have left Ukraine. She would stay with her parents. But she left to save her kids.”

Hope for the future

Maksymenko’s two children are still very scared even though they have left Ukraine. They ask her if someone is shooting whenever they hear loud noises when they are outside.

The children also ask about their father and when he will be coming since they miss him. Maksymenko is also missing her husband and vice versa. It’s difficult for them to speak since there is a nine-hour time difference, so while one’s day is ending, another’s just begins.

“She is lucky because she can communicate with her husband but not her parents … ,” said Kharchenko. “It is a real human desire to stay together as family, with husband, with parents, and kids will survive and kids will be happy.

“It look like regular wishes. Big houses (to) stay with your family and be happy together. She hopes to meet her husband and parents in the future … .

“It is the biggest heartbreak situation.”

Since Maksymenko plans to make Moose Jaw home, she is looking for an English teacher, free room and board for a few months, and daycare for her children. Moving into the city will allow her to hear English regularly and travel around Moose Jaw.

Anyone who wants to support Maksymenko financially can donate to Scotiabank, with the account number 60038 0305928.

For more information, call Amy Jane Lunov at 306-691-1300.