It has been 70 years since the guns on the Korean peninsula fell silent, a result of thousands of Canadians and other United Nations allies defending the democratic south from the Communist north.

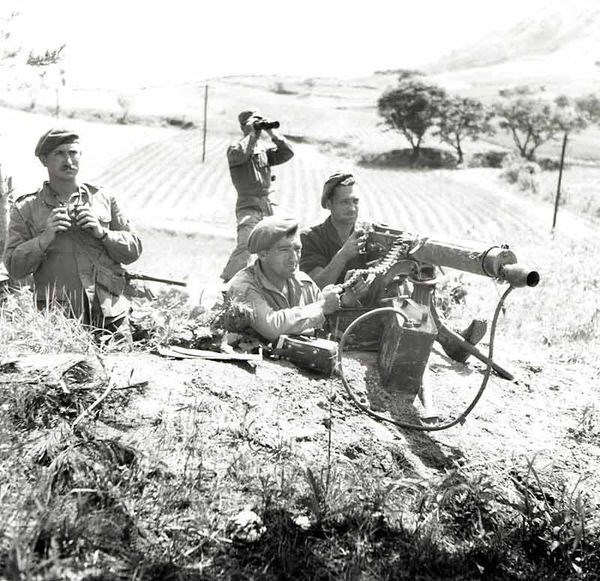

The Korean War — considered the “forgotten conflict” — started on June 25, 1950, when North Korea invaded South Korea. United Nations forces soon joined the fighting, which raged until an armistice was signed on July 27, 1953.

There were 26,791 Canadians who served on land, at sea and in the air during the bitter conflict, with more than 1,200 men wounded and 516 killed during the three-year war — Canada’s third-bloodiest overseas conflict.

The first Canadian group to arrive was the 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI), which landed at Busan, South Korea, on Dec. 18, 1950. Their first big fight came five months later.

The Battle of Kapyong — the most well-known battle of the war — occurred from April 22 to 24, 1951, when Communist soldiers launched a major offensive in that valley. For two days, nearly 700 Canadian troops defended crucial hills against roughly 5,000 Chinese soldiers.

Canadian veteran Gerald Gowing recalled, “We were surrounded on the hills of Kapyong and there was a lot of fire. We were pretty well out of ammunition and out of food too. We did get some air supplies dropped in, but we were actually surrounded.”

Holding the line was an impressive achievement but came at a cost. Ten Canadians were killed and 23 wounded, which could be considered relatively light given the fierce fighting there and a testament to the defenders’ skill and organization.

Other major battles included:

- Hill 355 from Nov. 22 to 25, 1951, when the Canadian regiments defended the front lines and pushed back heavy assaults

- Kowang-San from Oct. 22 to 23, 1952, where, in a battle that lasted 33 hours, the Royal Canadian Regiment held its position against Chinese forces. Afterward, several Canucks won three Military Crosses and four Military Medals for gallantry

- Hill 187 on May 2, 1953, which was the Canadian Army’s last major battle, in which the 3rd Battalion, the Royal Canadian Regiment endured constant enemy shellfire and wave upon wave of assaults

Three men with Moose Jaw connections are known to have died during — or because of — the Korean War, while others, such as Charlie Smith, returned home to tell their tales.

Cpl. Melvin Hugh Eugene Schwenneker was born on March 14, 1929, to Lincoln and Sadie Schwenneker. His parents later moved to Vancouver, British Columbia, while he eventually married Florence Gertrude from Swift Current.

Schwenneker was 17 when he enlisted in Regina on Dec. 2, 1946. He joined the PPCLI, and it was during a battle on June 21, 1952, when he was killed in action.

A newspaper article says he died when a cluster of three heavy mortar bombs hit his 18-man patrol near the front lines. The attack injured six other B.C. men.

“The 23-year-old father of a baby son was on his final patrol before coming home on rotation leave,” the article said, adding the mortar strike was a “fluke” since, according to Canadian Press correspondent Bill Boss: “Observers believe that the mortars weren’t fired at the patrol; that the enemy didn’t even know he was being attacked.”

The military buried Schwenneker at the UN Cemetery in Busan.

Lt.-Cmdr. John Louis Quinn was born on June 25, 1923, to Col. H.J. and Rosa Quinn; they eventually moved to Regina. He later married Grace Lillian Merrill and they produced a son, Charles Patrick.

Quinn enlisted in Regina in the Royal Canadian Navy (RCN) on April 2, 1942, and served in the Second World War. He remained with the navy after the war.

The military eventually gave him command of HMCS Iroquois — a Second World War ship recommissioned in 1951 — and, in the spring of 1952, he was sent to Korea and promoted to lieutenant commander that June.

Quinn successfully led his ship for five months before he was killed on Oct. 2, 1952, along with two other men — several others were wounded — after a North Korean shell struck their turret. Their deaths were the RCN’s first casualties of the war.

The Iroquois and a U.S. ship had bombarded a section of North Korean railway along the east coast shoreline for an hour. UN warships had pounded the track previously and the Communists were attempting to restore it for service.

As the two ships sailed away, shore batteries opened fire and a full salvo bracketed the Canadian vessel. Quinn, 29, and another sailor were killed instantly, while another died afterward.

The navy buried Quinn in Japan’s Yokohama War Cemetery.

He also received a post-humous “mention in dispatches” at home: “Throughout the whole period of Korean operations, until his death in action, he set a fine example of leadership in his quarters. His devotion to duty, courage and cheerfulness at all times were an inspiration to the gun crews he commanded.”

Pvt. William John Walch was born on July 26, 1930, to James Arthur and Pearl Violet; they later moved to Parr View near Melfort.

Walch enlisted in Regina on Oct. 18, 1951, and served with the PPCLI. It’s unknown where or when he was injured, but an article says he died at age 23 in Regina on Sept. 6, 1953 — nearly two months after the war ended.

A funeral service was held in Eyebrow three days afterward and he was buried in that community’s cemetery.