Three mothers are concerned about a particular type of marking system used in their children’s schools that they say negatively affects motivation and lacks clarity in reporting how students are truly doing.

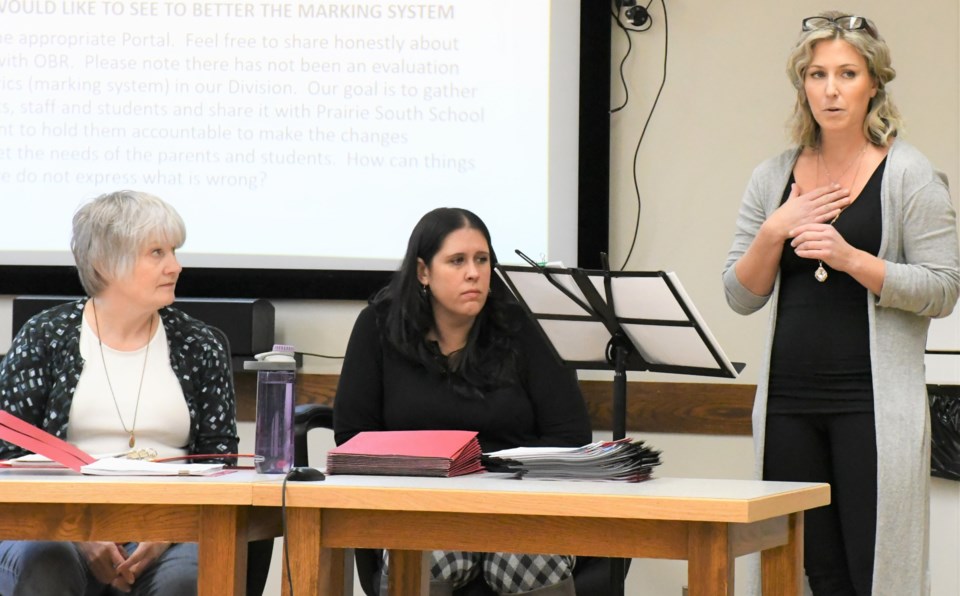

Jan Nelson, Cheryl Searle and Lindsay Newsham spoke to the Prairie South School Division (PSSD) board of education during its Jan. 7 meeting, where they shared their concerns with outcome-based education (OBE) and outcome-based reporting (OBR).

Nelson and Searle both served on Mortlach School’s school community council (SCC) from 2007 to 2015. Nelson’s children now attend school in Moose Jaw.

“We need real change and real modification because our kids only get to do this once,” said Nelson. “We know you mean well and are thinking of the best interests of students, but we are a case study. Study us. Let us be your research and hold yourselves accountable to address the concerns of families in Prairie South School Division.”

Helpful information

The presenters provided the board trustees with folders containing documents about outcome-based education and reporting, its history, how successful or unsuccessful it has been worldwide, a student’s PSSD report card with outcome-based indicators, the results of a survey that some parents, teachers, PSSD staff and concerned citizens answered, and a document from the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (FCPP).

According to the FCPP, outcome-based education — which is the foundation for the Saskatchewan curriculum — relies on a constructivist approach, which emphasizes student self-discovery with few expectations. Conversely, direct instruction is the traditional teacher-directed method where educators identify learning goals, make them clear to students, show students what they need to do, check for their understanding and provide time for students to have independent practice.

Struggling child

Nelson shared how her son struggled in Grade 3 while attending Mortlach School, a school “that is led by an extreme constructivist mindset.” She was concerned with his writing skills, so she worked with him at home to help him improve.

When her son moved into Grade 4, she attended a parent-teacher conference where the teacher shared a piece of writing her son had written that was exceptionally written. While that was positive, Nelson noticed misspelled words and punctuation errors, something she pointed out to the teacher and wondered if they would be corrected.

“And she replied, ‘No Jan, that is just small stuff,’” recalled Nelson.

When pressed about how her son would improve, the teacher said her son would learn to fix his spelling through his readings and through his school journey. This bothered Nelson, so she and her husband decided to move their son to a new school.

This year her son has a traditional-minded teacher who uses a red pen to point out spelling mistakes, something Nelson appreciates seeing. Her son also told her he now plans to start spelling words properly.

“That was the problem for us with constructivism: he wasn’t given an expectation and there was no consequence to slacking off,” she added, “and therefore, he didn’t do the quality of work that should be expected of him at his age … .”

PSSD’s grading practices

According to Prairie South’s grading practices document, effective grades must be consistent, accurate, meaningful and supportive of learning. The document says these indicators are used to communicate “grades,” which is the statement of student performance.

Consistency

In the division, marks are subject to the teachers’ opinion of what they can expect from the student, said Nelson. Principals decide with their staff when to implement the highest achievement indicator of exemplary (EX), but that is inconsistent from teacher to teacher and principals don’t have the resources to police what staff does.

Nelson’s 14-year-old daughter received an EX for her work in one class but didn’t receive the same mark in another class even though she had completed similar work. This inconsistency, noted Nelson, frustrates students and parents since some work that equals 100 per cent doesn’t always receive that grade.

Furthermore, parents can become confused about why their child is receiving an ME (meeting expectations; second-highest grade) in reading when the teacher has verbally communicated that the student is struggling.

Accuracy

Not all parents understand what the achievement indicators mean since the vocabulary of descriptors changes frequently, Nelson said. This could be because they don’t understand that achievement indicators are not a scale — one to 100 per cent — but are a checkmark of participation or completion.

For example, parents could say that ME does not communicate the depth and breadth of what students know. Instead, performance might be best measured if parents knew on which end of ME students were, but that would require the use of a scale.

Meaningful

Parents don’t understand the language of the outcome, which makes it meaningless and causes them to disengage from their child’s education, said Nelson. This includes her and her husband, who did not understand one of the outcomes for their son’s writing assignment.

Teachers’ comments have become important to help parents determine how their children are doing, she continued. But quality comments are not common and are only required for English and math. Furthermore, some parents have noticed teachers’ comments are copied and pasted between report cards.

“These generic comments increase the level of just how meaningless the reporting can be to parents and students,” added Nelson.

Supportive of learning

Nelson, Searle and Newsham believe when the first three goals are not being met, the fourth goal cannot be met either. Nelson pointed out the philosophy of OBE eliminates comparisons among students and also counteracts motivation, communication and engagement. She thought improvements in learning could not be shown without the use of a scale system.

“Scaling and measuring is part of our culture. Our society measures everything: days, hours, appointments, heights, weights, sports (and) work pay,” she added. “We work for a reward and we always will. It’s our natural tendency to compare ourselves with others.”

The three women provided more information during their presentation, which will be reported on in subsequent articles.