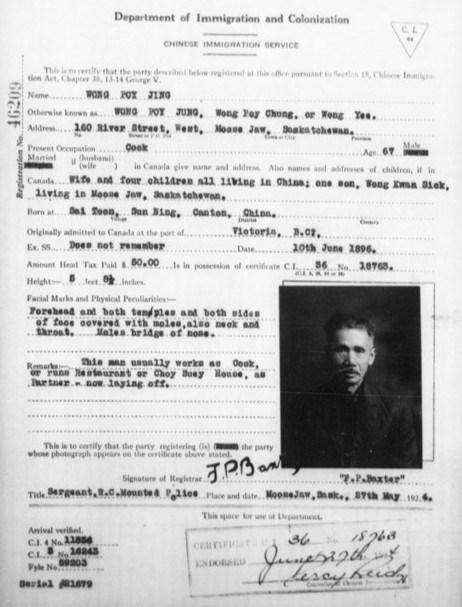

MOOSE JAW — On a spring morning in 1924, 67-year-old Wong Poy Jing walked into an office in downtown Moose Jaw and registered with the Canadian government. He gave his height — five feet, eight-and-a-half inches — his occupation, cook, and his address: 160 River Street West.

What he couldn’t list on the form was everything he had given up.

Like hundreds of others in Moose Jaw’s Chinese community, Jing had spent decades separated from his wife and children, working in restaurants and laundromats to support them from across an ocean. That year, he became one of 431 residents of Chinese descent in Moose Jaw forced to register under the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923 — better known as the “Chinese Exclusion Act.”

Author and historian Catherine Clement, who presented her book The Paper Trail in Moose Jaw recently, described the Act as one of the most humiliating and destructive policies ever inflicted on an immigrant community in Canada.

“Many of these men had lived here for 20, 30, even 40 years,” she said. “They paid the head tax. They paid their dues. And then Canada shut the door and told them they didn’t belong.”

The Act became law on Dominion Day — July 1, 1923 — effectively banning Chinese immigration and ordering all people of Chinese origin, including Canadian-born children, to register within 12 months or face fines, jail, or deportation.

In Moose Jaw, residents of Chinese ancestry complied. Records show that 416 of the 431 registrants were men. Just 15 were women, and 44 were children under the age of 18 — most of whom were born in Canada, yet issued C.I.45 immigration cards that explicitly stated they did not confer legal status upon them.

Three photographs were required per registrant, along with routine fingerprinting. Interrogations by the RCMP were common.

“Imagine how it must have felt to be rounded up for registration in your own city, when all you’ve done is try to run a business or work in a kitchen,” Clement told the audience. “It was devastating; it was dehumanizing.”

According to Clement’s research, at least 250 Moose Jaw registrants worked as cooks or restaurant staff. Dozens more were employed in laundromats or as merchants, tailors, and barbers — businesses that had long served the city, even while their owners were systematically excluded from full participation in Canadian life.

One of those men was Yow Yuk Yee, a 29-year-old cook at the Maple Leaf Restaurant on River Street West. He had arrived in Canada in 1913, leaving behind a wife and infant son in Hoi Ning, Canton, China. He paid the $500 head tax at the border — the equivalent of more than $10,000 today — just to enter the country. A decade later, he stood in a Regina police station to comply with mandatory registration. His file noted a burn mark above his right eye.

Another was Sang (Charlie) Chow, who arrived in 1899 and later opened a general store on Coteau Street West. He registered himself and his five children just before the deadline in June 1924. His son, Peter Chow, born in Moose Jaw, was issued a C.I.45 certificate — a document that denied him the same recognition as other Canadian children.

Peter would go on to raise a family, and today, two of his grandsons — Darin and David Chow — serve as judges in Saskatchewan. Their success stands in stark contrast to the institutional discrimination their great-grandfather faced.

“These stories matter because they’re ours,” Clement said. “They happened here. They shaped our community.”

While The Paper Trail features stories from across the country, Moose Jaw emerges as a powerful example of how the Exclusion Act affected life on the Prairies. Clement highlighted the city in her presentation, pointing to rare intermarriages — including three Moose Jaw men who married white women — and the disproportionate number of men forced to live alone.

Only six registrants in Moose Jaw lived with their wives. The rest lived as “married bachelors” — men with families in China they would likely never see again.

In 1924, articles in the Regina Leader-Post warned that the RCMP would begin rounding up Chinese residents for registration. National headlines compared the process to fingerprinting criminals. Many Chinese residents waited until the final weeks of the registration period, hoping the law would change — but it didn’t.

“Imagine reading that in the paper, (all while) just running your business and trying to live,” she said.

The Exclusion Act remained in place for nearly 24 years. Even after it was repealed in 1947, many of its impacts lingered. Families had been scattered, opportunities lost, and entire generations grew up not knowing what their parents endured.

“History doesn’t live in dates and legislation,” Clement said. “It lives in the lives of ordinary people — and in the paper trail they left behind.”