Although genealogy focuses on the history of family and humanity, the Moose Jaw Genealogical Society brought in a guest lecture to focus on the extensive history of the Moose Jaw River Valley and its changing landscape.

Rich Pickering has been doing his own research about the valley and the many different people who have called the area home for a number of years.

Pickering was a part of the committee that worked on renaming the Wild Animal Park to its new moniker Tatawâw Park, which means “welcome, there is room for everyone" in Cree.

For Pickering, the name is accurate, especially considering the land’s history.

“We thought that was fitting because there is room for everyone down there,” said Pickering. “Everybody has a story or connection to that place.”

He’s amassed an impressive knowledge about the river valley prior to the large-scale settlement of the community beginning in 1882 and collected plenty of evidence about the cultures who made this area home before it was even known as Moose Jaw.

Settlers came to Moose Jaw en masse in the early 1880s, settling along the CP Rail line in what is now the city of Moose Jaw, but this part of the prairie been inhabited for far longer than that.

The Moose Jaw River Valley is located within Treaty 4 territory and the traditional lands of the Métis, which means archaeological evidence covers nearly every part of the surrounding area.

Oral history names the area as a gathering place for many cultures, and remains have been found showing the presence of at least 26 distinct groups that dates back thousands of years.

“Basically, anywhere (in this area) you want to put a shovel in the ground, it’s an archaeological site,” said Pickering.

It can be difficult for amateur history-sleuths to do research on this time in the area’s history, considering the lack of paper documents from the period, but Pickering has looked back as far as he could to get a picture of what things were like in the valley.

He focused his presentation on the research he has done on how the landscape and population in the river valley changed since the 1850s, especially focusing on the Métis presence in the area.

Why are we called “Moose Jaw?”

The Moose Jaw River is mentioned in a few different expedition journals that predate the first official census in the area, including Henry Hill’s expedition in the 1850s, James Palliser’s survey mapping journey from 1857 to 1860, and the memoirs of Hudson Bay Company employee Isaac Cowie in 1868.

Several names are used to reference the river valley, including Moose Jaw Forks, Moose Jaw Creek, Moose Jaw Bone Creek, and the Turn — which references a specific curve in the river.

In all of his rabbit holes of research, Pickering still has yet to determine the exact reason that Moose Jaw sports it's unusual name, but he does have a theory.

He thinks that the story about a Red River cart breaking down in the area and having a wheel spoke replaced with a moose’s jaw bone is definitely not the origin story of the city’s name.

Rather, Pickering thinks that in one of the early European expeditions to survey the area — as early as the 1850s — an explorer was quizzing his Métis area guide on what this particular river called, to record in his journal.

Because these Métis guides spoke numerous languages and had a different accent, it's possible that they gave the explorer a Michif word for what they called the river, which was then written down phonetically by a European who didn't speak the language.

How the Métis adjusted as the area changed

The mention of Métis guides in these journals doesn’t necessarily mean they were living in the area, but Pickering found another way of proving that there was a significant Métis presence in the area during this time.

He discovered an HBC servant named Xavier Denomie, mentioned in Cowie’s memoir, who was known to offer lodging cabins to travellers on the Moose Jaw River. Denomie’s name also appears on the official listings for scrip claims from the federal government.

Denomie, along with many others, submitted his entire family for their scrip claims in this area, which shows that there was a Métis population that was, at the very least, wintering in the area and had a relationship with the HBC at that time.

Denomie is also mentioned in the official listings of homesteads in Saskatchewan, which are accessible through the Provincial Archives of Saskatchewan.

The first census of the area was a special census in 1884, just two years after settlers appeared in the area from down the rail line. Moose Jaw is listed as a sub-district and recorded just over 220 individuals of Métis descent living in the settlement.

Using a photo Pickering found of a local plow-salesman in the area surrounded by Red River carts, he theorizes that at this time, some Métis had begun working as freighters with their carts, delivering goods to buyers.

By 1901, just before Moose Jaw officially became a city, the Métis population had all but disappeared from the census records, although that’s likely because the time following Louis Riel’s rebellion meant identifying as Métis was unpopular and potentially hazardous.

An image taken in what is now Tatawâw Park, featuring Lakota chief Black Bull (front) alongside a group of Moose Jaw military and other Lakota peoples in 1885. (supplied)

An image taken in what is now Tatawâw Park, featuring Lakota chief Black Bull (front) alongside a group of Moose Jaw military and other Lakota peoples in 1885. (supplied) The Lakota encampment in the Moose Jaw River Valley

Tatawâw Park is also notably the area where a large number of the Lakota Nation settled, in an encampment that called the river valley home for decades.

In a tour of the park earlier this year, Pickering and historical author Ron Papandrea trekked down to their best estimate of where the Lakota camp was likely set up, based on photos and geography.

The iconic photo of Chief Black Bull — one of the powerful chiefs who took part in Custer’s Last Stand with the famous chief Sitting Bull — shows a distinct set of hills in the background, which can be matched to the ridge that borders Tatawâw Park.

The Lakota encampment is estimated to have been set up as early as 1883, and remained there for over 30 years, before a large portion of the group moved to the reserve land at Wood Mountain.

Some stayed, however, and the 1901 census in Moose Jaw recorded a number of Lakota and Sioux residents still in the area.

The Lakota camp is believed to have been located at this curve in the Moose Jaw River, although there would have been more brush and less trees in the 1880s.

The Lakota camp is believed to have been located at this curve in the Moose Jaw River, although there would have been more brush and less trees in the 1880s.The changing River Valley geography

Out of curiosity, Pickering took an interest in pinpointing exactly where Denomie’s renting cabins were located in the Moose Jaw River Valley, which led him on a hunt to determine why accounts of the river’s turns don’t quite line up with the current geography.

Using the Dominion Land Survey from 1881 and the official township maps from the 1890s, Pickering was able to determine what the river looked like in the mid-1800s and where the most travelled trails connected.

The Turn, referenced in so many expedition journals and the likely place where travellers camped because of its resources, is a part of the Moose Jaw River that no longer exists; it’s bee straightened out by human intervention.

Additionally, not all of the trails recorded on the Dominion Land Survey are necessarily fur trade trails but were certainly ones used for many years before the survey, crossing at the lowest and safest points of the winding river.

The landscape of the riverbanks through Connor Park — once called Kingsway Park — have also shifted as the area was developed.

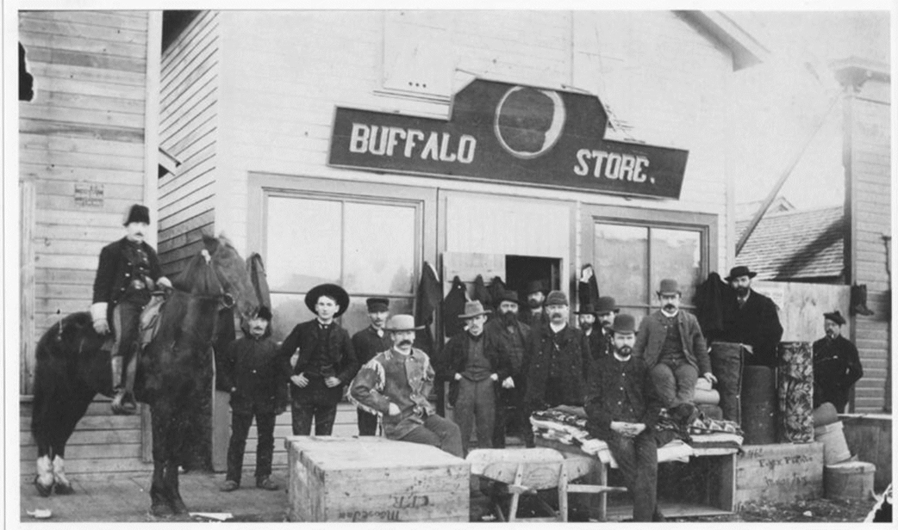

An image of the Buffalo Store in Moose Jaw in 1885, owned by merchant Félix Plante. (supplied)

An image of the Buffalo Store in Moose Jaw in 1885, owned by merchant Félix Plante. (supplied)Moose Jaw: bustling in 1885

Pickering also shared a handful of fascinating photos from Moose Jaw’s settlement-era: 1882 and onward.

A photo of the Halifax Provisional Battalion shows they were stationed in Moose Jaw in 1885 during the North-West Rebellion. This is also when a group of Sisters from Toronto travelled to the area to convert the Moose Hotel, which was located on the block of Main Street and High Street, into a military hospital.

Payment records from the federal government to citizens who offered services to military during the Rebellions offer an interesting look into living in Moose Jaw at this time as well — the Buffalo Store, owned by Félix Plante, was the place to go for candles, provisions, tobacco, blankets, and other necessities.

The Buffalo Store was also known for selling bison furs and bones, with some estimating close to a million buffalo in terms of bones were shipped from Moose Jaw.

By 1889, the township had published a brochure detailing all the commodities available in Moose Jaw. It listed the merchants, tradespeople, and services in town, as well as a thorough list of all the homesteaders in the district.

The brochure paints an idyllic picture of the community, but Pickering joked about why people actually settled in Moose Jaw, in the middle of the prairies.

“Why did a lot of people settle in Moose Jaw?” said Pickering. “Well, they ran out of money on the train, this was as far as they could afford to come.”

An image of the Sisters who provided care and the wounded Rebellion soldiers who were treated at the field hospital in Moose Jaw in 1885. (supplied)

An image of the Sisters who provided care and the wounded Rebellion soldiers who were treated at the field hospital in Moose Jaw in 1885. (supplied)What can we take from history

For Pickering, digging into the history of Moose Jaw is a passion project and sharing his knowledge has become an important part of the journey.

“It's just interesting to be able to raise an awareness of the history,” said Pickering. “Moose Jaw didn't start in 1882, there's a whole history going back 10,000 years, and for a lot of people there's still a connection to that history pre-1882.”

This knowledge is valuable, said Pickering, who has used it for presentations as well as to bring the BisonFest celebration back to the community.

He is also putting together another project about the history of the landscape, called the Northern Plains Heritage Centre — a self-guided virtual museum hopefully soon to be available online.

The virtual museum would join all of the other useful online resources that at-home historians like Pickering can use, which make this kind of research a bit more accessible.

“That's the advantage of the internet, you can find a lot of information that's scattered all over the place,” said Pickering. “It's in archives and libraries and books that have been digitized that haven't been looked at before, because they're really old books that you wouldn't normally have access to.”

The Genealogical Society in Moose Jaw hosts a new speaker each month, featuring different topics of interest related to genealogical research and history.