Chhoeut (Chi) Chhuon retired after 34 years at Fifth Avenue Collection, where he was a valued member of the family — but his story begins in Phnom Penh, Cambodia when the Khmer Rouge established a genocidal regime.

“What was it like having Chhoeut here? Well, there’s nobody more loyal than him, and he was good to all of us,” said Betty Butler, board chair at Fifth Avenue Collection. “From the day he started work here, he was just the best friend … We’ll miss him. We do miss him. He’s family, and so is his wife.”

The story of Chhuon’s time helping to build Fifth Avenue Collection, from its beginnings to the international success it is today, is an interesting one. However, it is overshadowed by how he and his family came to Canada in the first place.

The fall of Phnom Penh

Chhuon grew up near Phnom Penh, the capital of Cambodia and its most populous city. Founded in 1434, Phnom Penh became known as the Pearl of Asia in the 20th century, but when the Vietnam War started, the border between Cambodia and Vietnam became a flash point.

Every military force involved in the conflict crossed back and forth, and the country was devastated by the People’s Army of Vietnam, the Viet Cong, the South Vietnamese, the Khmer Rouge, and a massive American bombing campaign.

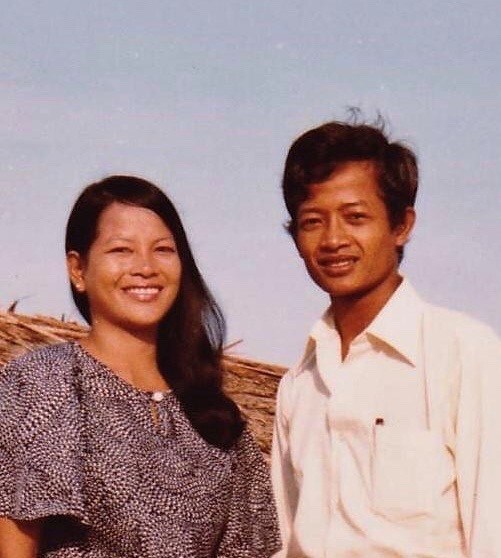

Chhuon and his wife, Kimly, lived through all of that. They still dream about it.

“Sometimes we just sit down and… we just don’t know how we got here,” Chhuon said. “We could have been dead so many times.”

In 1975, the population of Phnom Penh had swelled to between two and three million, mostly refugees from the countryside. The Communist Party of Kampuchea — another name for Cambodia —, popularly known as the Khmer Rouge, finally took the city and declared victory after over a year of indiscriminate shelling, deliberate starvation, and other terror tactics.

After the city fell, the Khmer Rouge forcibly evacuated the entire population of Phnom Penh in what is now known as one of the most brutal death marches in recorded history.

“They didn’t allow people to stay in the city. They just tell them to get out of the city. Rich, poor, whatever,” Chhuon said. “We had to go out to the country and do farming.”

Families were deliberately separated. People were grouped by age instead, including camps for children under 12 or 13. The Khmer Rouge’s stated objective was a new, agrarian society. Anyone from an urban area was made a member of the “New People” — a slave class condemned to hard labour.

Becoming New People

One of the Khmer Rouge mottos for these New People was: To keep you is no benefit. To destroy you is no loss.

“They only allowed us two meals a day,” Chhuon remembers. “We worked from sunrise to sunset … Then they have, like, five cups of rice and a big pot of water. That’s the food they feed us, every day. And that five cups of rice fed about 30 people.

“Every day, we see the bodies, the people dying. And nobody buried any of the bodies. Because we have no strength to do that.”

Chhuon’s wife worked at a children’s camp during the war. There were four or five women to look after around 500 children. There wasn’t enough food. Children died every day. And every night, the soldiers in the camp gathered a group of undesirables and took them away and shot them.

“If you’ve seen The Killing Fields,” Chhuon said. “Yes, that was terrible, and it’s sad — you feel it — but it’s nothing. It was much worse than that movie shows.”

The genocide killed 1.5 to 2 million people — about 25 per cent of all Cambodians.

Kimly and Chi met after the consolidated Vietnam invaded and overthrew the Khmer regime. That wasn’t the end of the country’s pain, though. A Khmer Rouge insurgency carried on for years. They fought the Vietnamese. And both Khmer Rouge and Vietnamese fought the American-supported “freedom fighters” on the Thai border.

Their first son was born while they ran from a refugee camp being attacked by Khmer Rouge. Bullets flew and people died around them while Chhuon’s wife went into early labour. They walked for three days with almost no food before a Red Cross truck asked them if they needed help.

“Yes, we need help,” Chhuon told them. They were loaded into the truck next to the wounded and sick. It was overloaded and bloody. That night, Kimly gave birth in yet another refugee camp. They had nothing.

An unexpected Canadian life

Two more sons were born in refugee camps over the next few years. Chhuon found work with the UN in Thailand, and applied to go to Australia. He spoke English, Cambodian, and Thai, and was a talented photographer.

At the last moment, belongings packed, ready for departure, something changed. Somehow, they found themselves on the way to Canada. They landed in Regina, and bussed from there to Moose Jaw.

The night they arrived in Moose Jaw, they had no money and no food — a familiar, uncomfortable situation. They sat in the cold rain outside the bus station until an employee came out to assure them they were allowed to go inside.

“We were very lost,” Chhuon said. “We were lost and lonely.”

Eventually, Chhuon got his job at Fifth Avenue Collection. He says that the people there are more like family than employers. He found new parents and new brothers and sisters.

Every few years, Chhuon and his wife go back to Cambodia, bringing money and help to their family and friends. That’s their retirement plan, too, although they will officially be living in Montreal with one of their sons.

Their three sons, and a daughter born in Canada, are all doing well. They have good careers. Chi and Kimly have six grandchildren, with another on the way.