MANITOBA CO-OPERATOR — Well, up to now, none of my discussions about severe weather has manifested in an outbreak of severe weather — but over the last few weeks, thunderstorms have brought some extreme rainfall events to a few areas.

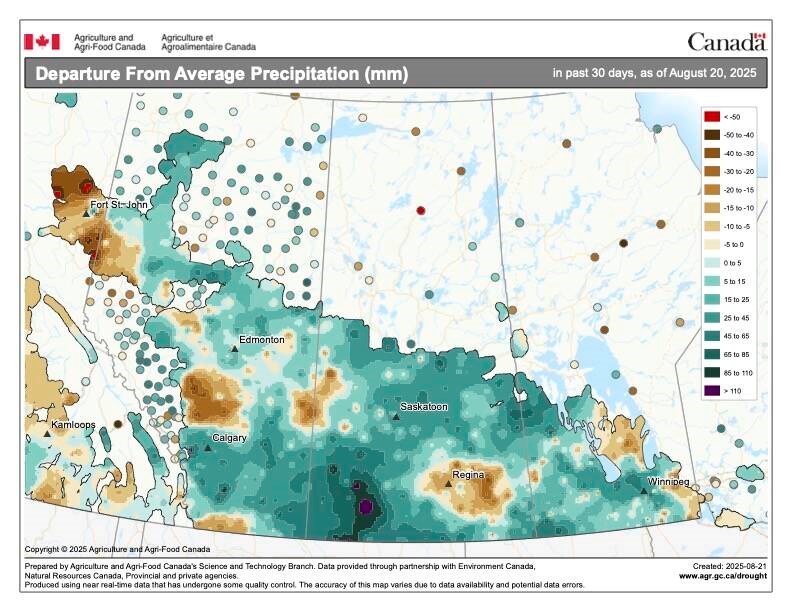

In particular, training thunderstorms brought upwards of 100 millimetres of rain to parts of southern Manitoba.

Recipe for rain

There are several factors that need to come together for an extreme rainfall event to take place. Sometimes you need more than just one factor, other times, if the factor is strong enough, you just need one.

The first factor is atmospheric moisture. If we are going to get heavy rain, there needs to be a significant supply of moisture in the atmosphere.

When warm, moist air masses interact with cooler air, it can lead to the condensation of water vapour and the formation of clouds and precipitation. Across the Prairies we experience the influx of moisture-laden air from different directions, such as from the Gulf of Mexico or the Pacific, which can contribute to the potential for heavy rain. For really extreme rainfall events, we need the atmospheric moisture to be deep, that is, a large portion of the atmosphere is moist.

This deep moisture is referred to as precipitable water and is measured by stating the amount of rainfall that would occur if all the moisture over a region fell as rain all at once. When there is a lot of deep moisture across our region, we can typically see this value in the 50 mm range, but that doesn’t mean this is the greatest amount of rain that we can see.

We can have plenty of moisture in place but still not see heavy or extreme rainfall. The second key component or factor is atmospheric instability.

Atmospheric instability refers to the condition in which warm, moist air at the surface is overlaid by cooler, drier air aloft. This creates an environment conducive to the development of thunderstorms and heavy rainfall.

As the sun warms the surface it heats the surrounding air, and it begins to rise. This rising air will cool, but if it cools at a slower rate than that of the atmosphere around it, then the air will continue to rise, eventually cooling to the point that condensation will occur.Remember the total precipitable water? Well, as that air rises, new air moves in horizontally that is also full of moisture. That air will eventually rise bringing even more moisture into the upper atmosphere to condense. This is why you can get much more rainfall that what the precipitable water value is.

Impact of Manitoba’s landscape

The next factor is confined to certain parts of the Prairies such as the Manitoba escarpment and further west to the Rocky Mountains, and it is topography and orographic lift.

While the Prairies are generally flat, there can still be variations in terrain that influence the behavior of storm systems. Even subtle changes in elevation, such as low hills or ridges, can play a role in enhancing rainfall. When moist air is forced to rise over elevated features, a process known as orographic lift occurs. As the air is lifted, it cools and condenses, leading to cloud formation and precipitation. This effect can enhance rainfall over certain areas of the Prairies that are situated in the path of prevailing winds.

A burst of heavy rain falls on a field on top of the Manitoba escarpment June 12, 2024, part of a string of severe storms that hit the region at the time. | Photo by Alexis Stockford

We can see this in Manitoba around the Dauphin/Riding Mountain region, but it is especially evident in Alberta when easterly winds push up against the mountains. This is one of the leading reasons behind the epic flooding that hit southwestern Alberta back in 2013.

Bringing the storm

Besides moisture and instability, the next biggest factor that contributes to heavy or extreme rainfall is storm dynamics. This is basically how a storm system behaves. Rainfall events come from different types of storm systems, such as fronts, areas of low pressure, and convective thunderstorms. Each of these storm systems have the potential to produce heavy or extreme rainfall, depending on their dynamics or how they behave.

The behaviour that contributes the most to extreme rainfall events is the speed at which they are moving. Simply stated, the slower the system, the greater chance of heavy rain. When a front or an area of low-pressure moves slowly, or even stops moving, which we refer to as stalling out, then the mechanism in place for producing rainfall just stays over one region.

Normally most rain producing systems have the potential to bring heavy rain; they just don’t stay over one place long enough. Even convective thunderstorms can stall out but that usually does not create conditions that create heavy rain, as a stalled-out storm will usually self-destruct over a short period of time. What is dangerous with convective thunderstorms is when “training” occurs, as Manitoba recently saw.

Primed for rain

Training is when a series of thunderstorms form and move over the same region. One storm will develop and bring heavy rain, as it starts to move off and self-destruct a second storm then quickly develops and moves in to replace the first storm, and so on. From the ground it will often seem like it is just one big storm that keeps on going. Heavy rain develops, there is a short lull and then it picks up again. Training thunderstorms can and have resulted in some of the heaviest amounts of rain across the Prairies.

An evening thunderstorm rolls through southwestern Manitoba in early August 2025. | Photo by Alexis Stockford

The last factor that we are going to examine is convergence zones. These are similar to topography and orographic lift as they are areas where winds from different directions come together, or converge, forcing air to rise. They can form nearly anywhere when winds of opposing directions meet. These zones can act as focal points for storm development and can lead to the formation of heavy rain-producing thunderstorms.

About the author

Co-operator contributor

Daniel Bezte is a teacher by profession with a BA (Hon.) in geography, specializing in climatology, from the U of W. He operates a computerized weather station near Birds Hill Park.

Related Coverage

Warmer and wetter future for Prairie farms

Prairie heatwaves and upper highs

Soybeans, peas flag under Manitoba drought conditions

The theories of tornado formation

Prairie fall weather outlook mixed for late summer and early fall